For a Soldier Who Died on Camera

(Catullus, Carmina LXV, “etsi me adsiduo defectam cura dolore...”)

Brother, my verse calls me to work.

I am too dull with regret to midwife

verses for the Muses. The foreign earth

lies heavy on you by that strange river.

I’ll never meet you, now, to spend

an hour or two in some tavern to hear

your story of your war. Out of regret,

unknown brother, I write for you

this paraphrase of Catullus to tell you

I held you in my mind beyond

the electron flicker of your dying.

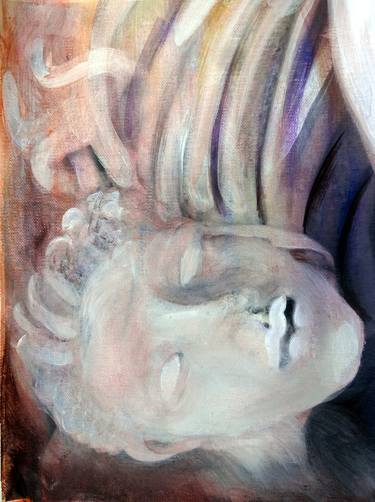

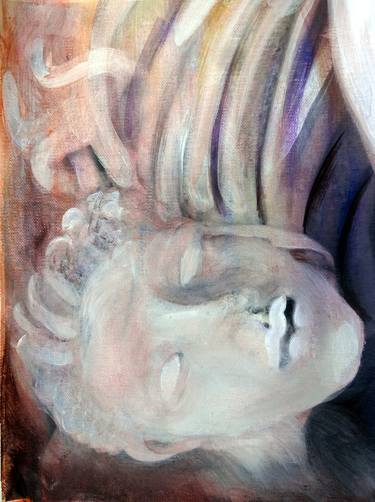

Dying Soldier -- Bezazel Levy

(Catullus, Carmina LXV, “etsi me adsiduo defectam cura dolore...”)

Brother, my verse calls me to work.

I am too dull with regret to midwife

verses for the Muses. The foreign earth

lies heavy on you by that strange river.

I’ll never meet you, now, to spend

an hour or two in some tavern to hear

your story of your war. Out of regret,

unknown brother, I write for you

this paraphrase of Catullus to tell you

I held you in my mind beyond

the electron flicker of your dying.

Dying Soldier -- Bezazel Levy

The life of Gaius Valerius Catullus has been pieced together from scattered references to him by ancient authors and from his poems. In the 4th century Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (St. Jerome, the translator of the Bible into Latin) said that he was born in 87 BCE and died in his 30th year, but some of his poems refer to events in 55 and 54 BCE. In the 7th century bishop Isidorus Hispalensis (Isidore of Hispalis [Sevilla]) preserved some of his output in the “Etymologiae,” an encyclopedia of extracts from classical antiquity that would have otherwise been lost but which, paradoxically superseded the use of many individual works which were thus not recopied and therefore became lost. In 966 bishop Ratherus of Verona (the poet's hometown) discovered a manuscript of his poems and reproached himself for spending day and night reading it. No more information on any Catullus manuscript is known again until about 1300. Probably the oldest manuscript containing the entire Catullan corpus dates to the last 1/3 of the 14th century. The 1st printed text was made in Venice in 1472, and a 2nd printed edition appeared in 1473 in Parma, which contained extensive corrections according to Francesco Puteolano. By then there were many manuscripts in circulation.Over the next century Angelo Ambrogini (“Poliziano”) and Joseph Justus Scaliger did further work on the texts; Scaliger in particular was the 1st scholar to apply sound rules of criticism and emendation and to change textual criticism from a series of haphazard guesses into a rational procedure subject to fixed laws. (His “De emendatione temporum,” 1583) was the 1st to include Persian, Babylonian, Egyptian, and Jewish history to Greek and Roman accounts.) Catullus' poems are preserved in 3 manuscripts that were copied from 1 of the 2 copies made from the lost manuscript discovered ca. 1300. Standard anthologies contain 116 carmina, though the actual number slightly differs in various editions, and a few fragments quoted by later editors but not found in the manuscripts show that additional poems have been lost. Far more than for other major classical poets, the text of Catullus' poems is in corrupt condition, with omissions and disputable word choices in many poems, making textual analysis and even conjectural changes important.

ReplyDeleteCatullus spent the year 57 to 56 BCE in Bithynia serving on the staff of Gaius Memmius, a poet who (according to Publius Ovidius Naso) wrote erotic poems like Catullus. While in that position Catullus traveled to the Troad to perform rites at the tomb of his older brother Hortale, an event recorded in “Carmina LXV:”

Hortalus, though through unremitting pain concern draws me,

who am exhausted, from the Muses, and my mind cannot produce

their sweet fruit, my very thoughts surge like waves for

such troubles— for recently a wave flowing from the sea of

Lethe has washed my brother's pale little foot, which,

removed from our eyes, the Trojan ground crushes under the

shore of Rhoeteum... My brother, dearer than life, will I

never look upon you hereafter? No, but certainly I'll always

love you: I'll always sing solemn poems about your death,

which Procne will sing along with me under the dense shadows

of branches as she groans the prophetic utterances of Itys,

removed by death. But in such bouts of grief, Hortalus, I

nevertheless send you these translations of Callimachus,

lest perchance you should think that your words, entrusted

in vain, have slipped from my mind to the wandering winds,

just as an apple, a fiancé's secret pledge given, rolls

forth from his maiden's chaste lap because the apple, having

been placed under the voluptuous dress of the girl who

unhappily has forgotten, is shaken out when she suddenly

jumps up at her mother's approach, and is suddenly thrown in

a fall to the ground as a self-conscious blush runs over her

unhappy face.

--tr. Brendan Rau