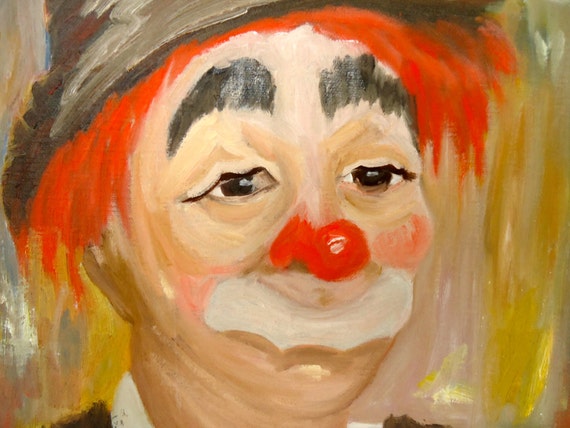

The White Clown

I

am the white clown, who travels

from

village to town, who says little

and

preaches much. You laugh at me

cry

for me, feel the pains that I

have

endured for you, walked steps

upwards

and downwards for you—

the

dancing clown, harlequin’s laughing

clown,

the stage walker who died in a duel

one

snowy morning, who was not resurrected

on

Easter, who fled with the demon horsemen.

Our

family circused for generations.

Poppy

died on the high wire.

Before

his fall, we crossed deserts

moved

to the mountains where

Swiss

cottages dotted the miraculous lake.

We

fished, and we caught many fish, which

we

shared with the strangers who had

come

to hear my message.

We

divided the loaves.

Crowds

grew and followed us.

We

traveled in their lands and then

into

other lands, the wagons swaying

the

lanterns’ lights twinkling in the darkness.

My

Venus sat beside me, pouring wine

into

my cup, looking toward heaven

her

hand squeezing my thigh.

She

was young and beautiful, with

auburn

hair, green eyes, long legs.

Her

walk could drive a man wild.

Great

masters have seen her as ugly

as

a haggard old woman without teeth

as

lovely as I. She was not repentant

did

not wash my feet. Instead she gazed

out

at me from Botticelli’s canvas and

held

my hand as we stepped into the ocean.

We

rode the waves together, called

upon

Poseidon to bring us his chariot.

Then

we left the old man with his nymphs.

In

the spring, dogwoods blossomed.

The

flowers grew into leaves.

Our

caravan disbanded.

I

gave up mandolin and turned

to

three rings, performed indoors

painted

my nose, wore striped pants

lost

my hair as well as my waistline

practiced

celibacy.

It

was for you, all for you

-- Red Skelton

“The White Clown” should be viewed as an Easter commentary, especially in its first stanza (despite the explicit reversal at the end of the stanza), the sidelong allusions in the second stanza (the deserts, the loaves and fishes, the large crowds, even the reference to Poppy dying on the high wire) and, of course, the poem’s closing line. However, it is not an Easter allegory; it merely uses the Christian motifs as a resonant background to his personal tale of love and sacrifice.

ReplyDeleteSandro Botticelli was a 15th-century Florentine painter. His illustration of the first printed edition of Dante’s “Inferno” was a seminal literary-artistic event, but he is best known for his painting, “The Birth of Venus” (portrayed as “young and beautiful, with auburn hair, green eyes, long legs” emerging triumphantly from a scallop half shell on the shore). Under the influence of the puritanical Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola, Boticelli first turned from decorative to devout art and then ceased painting altogether, perhaps even going so far as burning his own paintings in the infamous Bonfire of the Vanities in 1497, when moralistic mobs collected and destroyed thousands of books, artworks, mirrors, musical instruments, fine clothing, playing cards, cosmetics, and other vain, idolatrous objects.

Coincidentally, in “Corteo,” a Cirque du Soleil extravaganza, the White Clown, a would-be authority figure, opens the door to the magic of the circus for the Dead Clown, who watches his own funeral taking place in a carnival-like atmosphere.