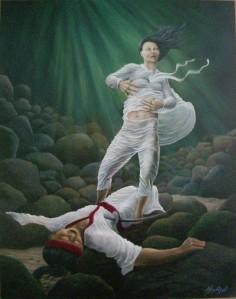

Chinju

(for Non-gae)

On this rock we sang

were

lovers for the cause

I

was the waitress-in-waiting

My

ringed hands locked

around

your waist

forever.

The

river of blood swallowed us

swept

up by currents

under

the stone bridge

we

could not turn back

and

you could not climb out

in

your heavy armour

to

the fortress wall

to

dance with wine

and

drink my people’s blood.

I

could not dance

under

stars again.

When Nongae was four, her father, a scholar named Ju Dalmoon, died, and her mother kidnapped her from the control of her in-laws. The mother was tried but found to be blameless by Choi Kyonghwe, a local magistarte. Later, after three years of rigorous training in poetry, dance, music, and art, Nongae became a certified kisaeng; though these women were officially servants of the state and were often used to entertain foreign dignitaries, they had the lowest social rank, “cheonmin” (“vulgar commoners”). At 17, Choi became Mongae’s gibu (“husband”), and, as his concubine, she moved into his home in Jinju, a city in South Gyeongsang Province, South Korea. Meanwhile, before Toyotomi Hideyoshi unified Japan, Kyōgoku Takumi murdered one of the Mōri clan’s sword instructors and his daughter. His widow, surviving daughter, and grandson recruited one of his retired former students, Keyamura Rokusuke, to avenge his death, but Kyōgoku refused his challenge due to Keyamura’s low caste. However, after demonstrating his skill and power in a series of sumō matches, Keyamura became a retainer of Katō Kiyomasa, one of Toyotomi’s relatives and chief generals. Now, as a samurai renamed Kida Magobee, he again challenged Kyōgoku and slew him.

ReplyDeleteIn 1592, Toyotomi invaded Chosun (Korea), with Katō as one of the three senior commanders; Katō took Seoul, Busan, and other cities, and defeated the last of the regular Korean troops at the Imjin river. In October, with 20,000 troops, Hosokawa Tadaoki marched against Jinju, a strategic stronghold that defended Kyongsang province; Japanese control over it would allow easy access to the ricebelts of Jeolla province and gave them a position from which to attack Gwak Jaeu's Righteous Army guerillas (composed of peasants, scholars, former government officials, and Buddhist warrior- monks). Jinju was defended by Kim Simin’s 3,800-man garrison. After three days of fighting, Kim was seriously wounded in the head and his troops were running out of ammunition, but they had inflicted heavy causalties against Jpaanese assaults. That night Gwak arrived with 3,000 reinforcements; Hosokawa was fooled into thinking it was a much larger force and withdrew. Nevertheless, the following year, the Japanese returned, under Kida’s command. The Korean general, Hwang Jin, held out for 10 days, but Japanese sappers, using an armored :tortoise shell cart,” finally breached a section of the wall, and Kida took the city, executed the defenders and civilians including Choi, and ordered the kisaeng to serve his officers at a victory celebration at the Chokseongnu pavilion on a cliff overlooking the Nam river. During the festivities, the 20-year-old widow Nongae led Kida to the cliff for an embrace, locked her fingers together with her rings, shouted “Uiam,” and jumped backward into the river, killing them both. The spot is now memorialized as Uiam, "the rock of righteousness,” and there is a shrine to her memory near Chokseongnu, in central Jinju. It is said the festival “Uiam Byeolje” took place every June, but memorial services in her honor did not begin until the late 19th century. However, since 2002, a Nongae festival has been held every year to celebrate her and the 70,000 regular and guerrilla troops who were slain defending Jinju during the seven-year Imjin War. And maybe neither story is quite true! No contemporary source mentioned Nongae, and later accounts did not name the general. Various manuscripts of the “Imjillok,” a relatively early account, falsely identified him as either Katō or Toyotomi. The first “historical” identification of Keyamura/Kida as the general was in Bak Jonghwa’s “Nongae and Gyewolhyang” in 1962, though Tamagawa Ichirō had made the same claim in his novel “Keijō, Chinkai and Fuzan” in 1951. On the other hand, Kida Magobee was a real but rather obscure person, who was inceed one of Katō’s retainers, and his family continued to serve the Hosokawa clan that superceded the Katō clan as the rulers of Kumamoto until the end of the shogunate. According to a mid-17-century biography of Katō, the “Kiyomasa-ki,” Kida was killed in battle against the Jurchens (Orankai) on the Manchurian border in 1592, but. Japanologist Choi Gwan has found a letter from Katō to Kida (and others) that dated about two months after his supposed death. A manuscript about Keyamura Rokusuke copied in 1716 and 1902 claims that he was the son of a rōnin (a samurai who has lost his retainership), distinguished himself as an unrivaled warrior in the Korean war, and. then returned to his home village and died at the age of 62. The story recounted here is a summary of various dramas about the emblematic farmer-turned-samurai who demonstrates filial piety and incredible strength, especially “Hiko-san Gongen chikai no sukedachi” by Tsugano Kafū and Chikamtsu Yasuzō, which was first performed as a ningyō jōruri play in 1786 and then adopted as a kabuki play the next year. It is not known how closely it reflected any historical fact.

ReplyDelete