Love’s Whipping Boy

Hellos are kinder than goodbyes,

although goodbyes are in them.

The death of couples

is the closing of the door

between them

from one side

and/or the other.

Half a couple talks

to him or herself

afterwards at first

in an awkward way

just to stay in practice

and hold the void at bay.

Silence is a major god

sometimes at war with solitude.

"I loved you" is hard to say,

a concession that it’s over.

It was always hard to hear.

“Who loved whom?”, the silence asks.

The myths of muteness

lie deep as broken bone,

set without a proper cast

by surgeon with less skill

than rusty time,

suturing with promises

which tend to come undone,

hobbling one content to walk,

but not dance again,

having slipped on broken ice.

The persevering heart,

love’s whipping boy

or girl, as the case may be,

one of the softest parts of us,

this boneless muscle,

as vulnerable as we let it be

to sucker-punch and perfidy,

what can be done to heal it

from the double brunt

of offense and injury?

What salve, what balm

would comfort and relieve it,

not just this time,

but also in the longer later?

To mend it, should one

marinate with love

to ease and soften

or pickle it in brine,

to tan it into leather,

toughen into shield?

Ossification

is the choice of some,

for, like vasectomy,

it can sometimes be reversed.

Those who’ve paddled

to the bitter end

of Love’s one-way Tunnel

may choose petrifaction,

preferring stone to bone.

Let’s linger with the heart,

for it has stuck with us,

to comfort if not heal it.

It sorely needs repair,

but can’t afford to rest

or worse, just stop.

Quiet harmony can be restored

by a simple tune-up

following eviction:

time to throw the squatter out,

due process’s time has come.

The volume now turned up,

the message is quite clear,

the sheriff’s at the door

where, although it’s mine,

he’s not serving me.

Why is it,

when we’re wounded,

shot in the back or heart,

we tend to take the blame

when the shouting’s done

and the silence claims us?

I thought I was receiver,

but am transmitter, too,

donor and donee

of contaminated blood.

As actor,

I must play all the roles

because I am the playwright

and director, too.

Here on the stage

what have I been, but target

for an audience of one?

What is it that I’ve done,

what crime?

What is the punishment,

for crimes of self on self?

Whatever crime,

I can’t throw the first stone,

and will not hurl the last.

I’ve done the time.

Parole, probation, pardon,

amnesty, whatever . . .

Escape,

when I release myself

I’m free.

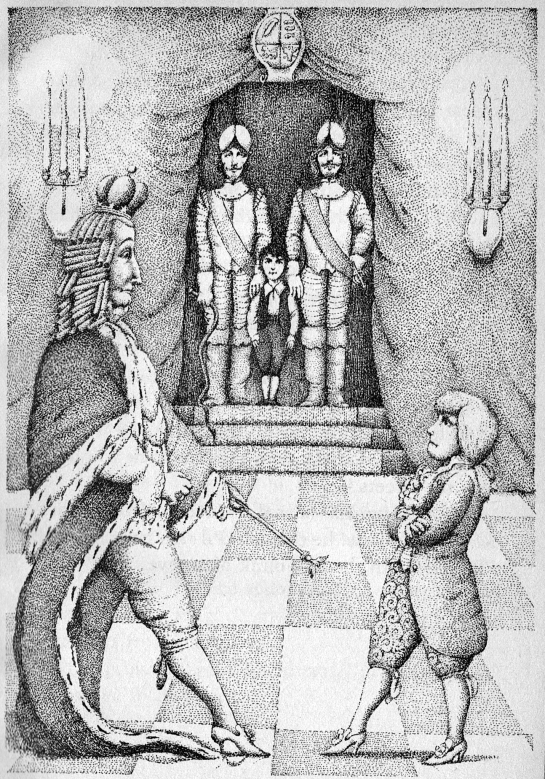

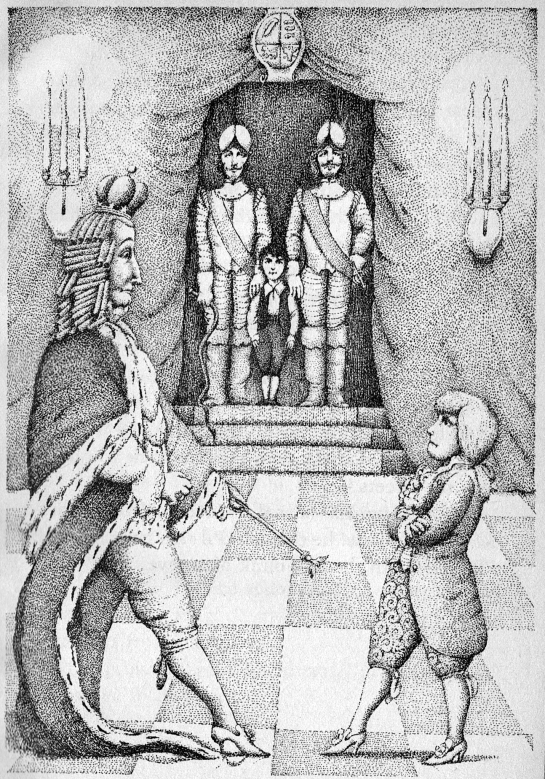

Edward and his Whipping Boy (ca. 1545)

The Whipping Boy -- Petr Sís

Hellos are kinder than goodbyes,

although goodbyes are in them.

The death of couples

is the closing of the door

between them

from one side

and/or the other.

Half a couple talks

to him or herself

afterwards at first

in an awkward way

just to stay in practice

and hold the void at bay.

Silence is a major god

sometimes at war with solitude.

"I loved you" is hard to say,

a concession that it’s over.

It was always hard to hear.

“Who loved whom?”, the silence asks.

The myths of muteness

lie deep as broken bone,

set without a proper cast

by surgeon with less skill

than rusty time,

suturing with promises

which tend to come undone,

hobbling one content to walk,

but not dance again,

having slipped on broken ice.

The persevering heart,

love’s whipping boy

or girl, as the case may be,

one of the softest parts of us,

this boneless muscle,

as vulnerable as we let it be

to sucker-punch and perfidy,

what can be done to heal it

from the double brunt

of offense and injury?

What salve, what balm

would comfort and relieve it,

not just this time,

but also in the longer later?

To mend it, should one

marinate with love

to ease and soften

or pickle it in brine,

to tan it into leather,

toughen into shield?

Ossification

is the choice of some,

for, like vasectomy,

it can sometimes be reversed.

Those who’ve paddled

to the bitter end

of Love’s one-way Tunnel

may choose petrifaction,

preferring stone to bone.

Let’s linger with the heart,

for it has stuck with us,

to comfort if not heal it.

It sorely needs repair,

but can’t afford to rest

or worse, just stop.

Quiet harmony can be restored

by a simple tune-up

following eviction:

time to throw the squatter out,

due process’s time has come.

The volume now turned up,

the message is quite clear,

the sheriff’s at the door

where, although it’s mine,

he’s not serving me.

Why is it,

when we’re wounded,

shot in the back or heart,

we tend to take the blame

when the shouting’s done

and the silence claims us?

I thought I was receiver,

but am transmitter, too,

donor and donee

of contaminated blood.

As actor,

I must play all the roles

because I am the playwright

and director, too.

Here on the stage

what have I been, but target

for an audience of one?

What is it that I’ve done,

what crime?

What is the punishment,

for crimes of self on self?

Whatever crime,

I can’t throw the first stone,

and will not hurl the last.

I’ve done the time.

Parole, probation, pardon,

amnesty, whatever . . .

Escape,

when I release myself

I’m free.

Edward and his Whipping Boy (ca. 1545)

The Whipping Boy -- Petr Sís

Beginning with the Tudor dynasty, whipping boy was an established position at the English court during the 15th and 16th centuries, kept for the purpose of beating him when the crown prince did wrong. Though whipping boys were sometimes orphans of foundlings, they were often high-born companions of the royal princes and shared many of the privileges of royalty. It was considered a form of punishment to the prince that someone he cared about was made to suffer. In 1609, James I declared, "The state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon earth; for kings are not only God's lieutenants upon earth, and sit upon God's throne, but even by God himself they are called Gods." Since God imposes the monarchy, and the prince would be an extension of that lineage, no one but the king could be worthy of punishing the prince. James' heir was Charles I, whose whipping boy was his close friend William Murray, whom Charles ennobled as first earl of Dysart in 1626.

ReplyDelete