LIPS

Port of call and of taste-buds

Ushering in stuffs that matter

Lighting up with smiles

Of fancy, fascination or beyond

And to vow along the vowels

I and u with aa and ee and oh!

To celebrate this life or

To play survival games

Of earthly cravings?

Or pout hieroglyphics of love

And shades of desire, out there

In moonlit fascination!

To kiss and make up

So too for a one-night stand

To map layers of affection,

Not surmised by a

Freud or

Jung

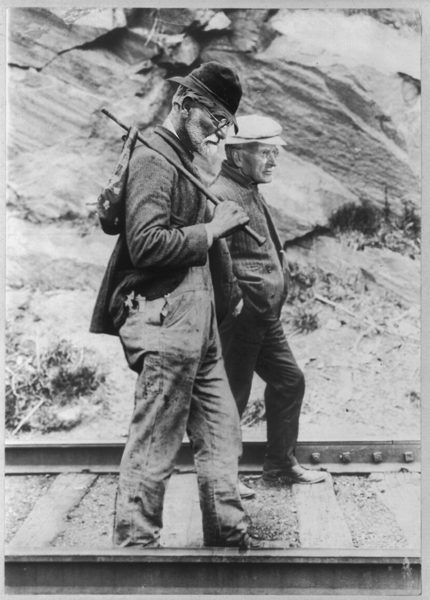

Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, 1908

In 1906, 31-year-old Carl Jung sent 50-year-old Sigmund Freud a signed copy of his new “Studies in Word Association” that relied heavily on Freud's own work. Just six years before, Jung, at the beginning of his career at the Burghölzli psychiatric hospital in Zürich with Eugen Bleuler (who was already in communication with Freud) was deeply inspired by the publication of Freud’s revolutionary “Die Traumdeutung“ (The Interpretation of Dreams), which introduced his theory of the unconscious and discussed what would be called the Oedipus complex. Six months after getting Jung’s book, Freud sent him a collection of his own recent essays. When they finally met, their first conversation lasted more than 13 hours. As their relationship developed, Freud described Jung as his “heir,” as "my successor and crown prince," as "spirit of my spirit," even as the “Joshua to my Moses, fated to enter the Promised Land which I myself will not live to see.” In 1908, Jung became editor of the new Freudian journal, “Yearbook for Psychoanalytical and Psychopathological Research,” and the following year they traveled together to the US to promote their psychological ideas, spending three months touring and lecturing. However the close contact and exhausting conversations exposed ideological differences that began to tear the friendship apart, mainly centered on their diverging concepts of the unconscious. Jung agreed with Freud's model of the “personal unconscious” as a repository of repressed emotions and desires but also proposed a deeper “collective unconscious“ where the archetypes resided. The rift began during a session of mutual dream analysis; Freud refused to answer Jung’s basic psychoanalytic questions about his dream about his wife and his sister-in-law, and Jung thought Freud misinterpreted the significance of his own dream about two skulls. Freud dismissed Jung’s interest in religion and myths as being “unscientific,” and Jung became embittered over the rejection of his ideas and began to spread rumors that Freud had once impregnated his sister-in-law. In 1912, Freud wrote to his former colleague proposing “that we abandon our personal relations entirely.” However, that year at a conference in Munich, when Freud fainted during Jung’s discussion of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep IV, Jung carried him to a nearby couch. Their final meeting was at the Fourth International Psychoanalytical Congress in 1913, when Jung’s talk on psychological types (introverted and extraverted) clearly introduced some of the key concepts that divided Jung’s “analytical psychology” from Freud’s “psychoanalysis.” Their mutual infatuation and ultimate estrangement strongly resembled many sexual histories, especially between two people of divergent ages and statuses. Perhaps the process can best be understood in terms of the concept of “projection” that Jung’s wife Emma developed. At the beginning of their relationship, Freud felt embattled and rejected by the psychological establishment, even as he became concerned about his own mortality and reputation in the future. Jung saw Freud as a father figure and was ambitious to advance his transformative concepts into the mainstream. Each imagined the other to be the “perfect partner,” the one to build a future on. For a time, each stimulated, inspired and energized the other with new possibilities. But Jung was not prepared to remain forever in the master’s shadow, despite Freud’s frequent attempt to reconcile.

ReplyDelete