Goddesses & Godlessness

Some feel best with goddesses

Or godlessness

To beat the odds

Of death’s finality,

Life’s unpredictability.

Where stand I with jumping mind,

A monkey mind?

Something in it knows it’s trying;

Something knows the I that’s eyeing

Cycles of existence,

Phases and the way life wends and winds

And weaves and threads

The paths that seem to be

Reality.

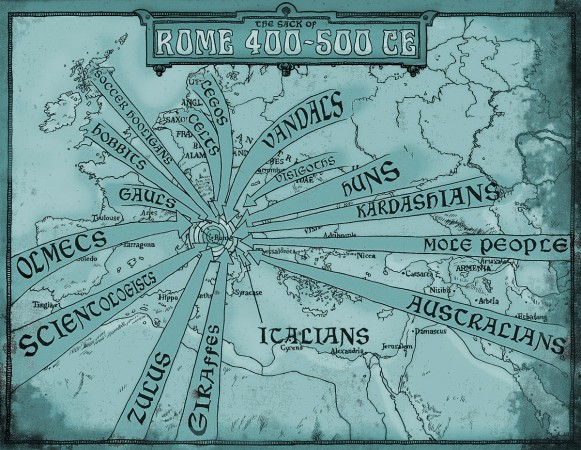

All roads lead to Rome,

Or do they?

Tabula Peutingeriana

"All Roads Lead to Rome" refers to the fact that many routes can lead to a given result. It is the modern reading of a medieval statement, apparently originally a reference to Roman roads in general but especilly to the Milliarium Aureum (Golden Milestone), a monument, probably of marble or gilded bronze, erected in 20 BCE near the Templum Saturni (Temple of Saturn) in the central Forum by Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus. in his role as curator viarum. All roads were considered to begin at this monument, and all distances in the empire were measured relative to it. At least 29 great military highways radiated from the capital, and its 113 provinces were interconnected by 372 great roads comprising more than 400,000 km (250,000 mi) of highway; over 80,500 km (50,000 mi) were stone-paved.

ReplyDeleteIn 1494 in a library in Worms, Celtes (Konrad Meissel) discovered 11 parchments scrolls measuring .34 X 6.75 m which, when assembled, was a planisphere of the known world from Britannia to India. The localities are connected by roads with distances marked in Roman numerals indicating the miles (1480 m) or, west of Lugdunum (Lyon), indicating the Gallic leagues (2220 m). However, the Italian peninsula seems to extend from west to east and Rhodes is close to the area of Tel-Aviv; like a modern subway map, the routes were drawn to show the distances and the crossroads in a clearly readable form without taking into account the scale or of the exact geographical orientation. It was given in 1507 to Konrad Peutinger and is thus known as the Tabula Peutingeriana. It was copied from an earlier copy in 1265 by a monk from Colmar, and was probably an accumulative work that was updated on different occasions over large intervals of time. The oldest information goes back to before 79, the year Pompeii was destroyed. Large cities were represented by thumbnails of variable size, some principal cities by walled spaces; cities were indicated by two big houses, towns by one, and some religious temples and sanctuaries were shown. The metropolises, Roma, Constantinopolis, and Antiochia, were pictured by personifications known as female tychai, the “fortunes.” The Roman tychoi is seated on a throne and clothed in imperial purple, holding a globe and a sceptre. Constantinoplis is also seated in imperial purple too, with a helmet on her head and a spear in her hand. she looks west and moves her hand in that direction, and a statue of an emperor on a column guards her entry. The biggest feature on the map, Antiochia, the “See of the East,” holds a spear and has a naked boy under her left foot, symbolizing the Orontes river. But if all roads led to Roma, what would one do upon arriving there? When Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis (St. Augustine) was puzzled about liturgical protocol, which varied from place to place, his mentor bishop Aurelius Ambrosius of Milano (St. Ambrose) advised him, "When I am at Rome, I fast on a Saturday; when I am at Milan, I do not. Follow the custom of the church where you are." Or, as the English say, "When in Rome, do as the Romans do."