I

I am a broken poet

with a-c-b-d,

I mean a-b-c-z, uh

My thoughts, disjointed;

seriously struggling to make

sense,

coming, going, jumping,

crawling

out of an aching head.

I am a broken verse

I like to be a ...

diving and ... all along,

dying at every attempt

to make musical melody

in lieu of melodramatic

malady.

I am my father's son.

Last I saw him, I was

three,

munching a bag of flakes

he claimed to bring from hajj.

I am a nonsense poem

but somehow you are glued to

me,

waiting to unearth

-unravel

-unleash the meaning

I bare.

I am a lover's woe,

coming when the bliss is

sweetest,

leaving when the cry is

saddest

for yet a little pat, a little

tap,

a little moment of crazy

upsurge,

wild electric frenzy.

I am the hunter's 'gamed'

game,

waiting to haunt back he who

hunted

when dinner is nearly over,

and

wives clutter in lively

chinwag,

I will enjoy the yelp, the

roll, the thud

as he falls with his damaged

throat,

perforated by my bones.

I am nothing

Don't waste till you catch me.

The answer on your lips,

when in silent wonder, you

leave men to torturous

ponder.

I, I, I

I am you

when I want and please to be.

Now, you can go to bed,

pray your soul be fed,

rhythmic morsels, redeeming

bread

to fine-tune your, your,

your

b-b-broken self.

For now, I rest my wearied

soul

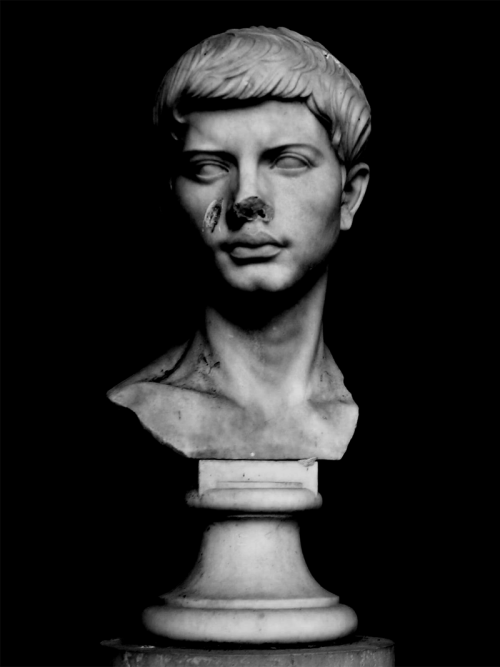

two busts of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro was a 1st-century BCE poet who revolutionized Latin poetry with his "Eclogues" (or "Bucolics"), the "Georgics," and the epic "Aeneid." A number of minor poems, collected in the "Appendix Vergiliana," are also sometimes attributed to him. He may have been born in the village of Andes, near Mantova, from a humble family according to the 5th-century write Macrobius Ambrosius Theodosius. His friend and editor Lucius Varius Rufus wrote his no-longer-extant biography, which may have been available to the historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus when he wrote "De Poetis" a century later as well as to Macrobius' contemporaries Maurus Servius Honoratus, who wrote "In tria Virgilii Opera Expositio," a set of commentaries on him (which happened to be the first book printed in Firenze (by Bernardo Cennini in 1471), and Tiberius Claudius Donatus, whose "Interpretationes Vergilianae," which was rediscovered in 1438 and saw 55 printed editions between 1488 and 1599. Of poor health and a shy disposition (his nickname was Parthenias ["maiden"], he probably started writing poetry while a student at the school of Siro the Epicurean at Napoli. The "Appendix Vergiliana," attributed to the youthful Vergilus by the 5th-century grammarians, include 14 short poems (the "Catalepton") and the "Culex" (Gnat), a short narrative poem that was attributed to him in the 1st century. Traditionally he began writing the 10 "Eclogues" (selections) in 42 BCE and published them ca. 39–38 BCE; they were modeled after the bucolic hexameter poetry of the 3rd-century Grek poet Theocritus. According to legend, they were written after Octavianus confiscated land (including Vergilius' estate near Mantova) to pay off his troops after his victory at Philippi. Before 37 BCE Vergilius became associated with Octavianus' close advisor Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, who sought to rally literary figures, including Varius Rufus, Sextus Propertius, and Quintus Horatius Flaccus, to bring the leading families away from their support of Marcus Antonius and over to Octavianus' side. Upon Maecenas' urging Vergilius spent the next decade or so on the four books of the hexameter poem the "Georgics" (On Working the Earth), a manual on running a farm. The poet and his patron took turns reading the verses to Octavianus after his defeat of Marcus Antonius at Actium in 31 BCE.

ReplyDeleteAccording to Propertius, after Octavianus became emperor Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus in 27 BCE he commissioned Vergilius to compose the "Aeneid," a 12-book epic poem in dactylic hexameter that detailed how his ancestor Aeneas fled the sacking of Troy and founded the city which eventually became Roma. Vergilius spent the last 11 years of his life (29–19 BCE) on it. The poet was alleged to have recited Books 2 (on the hero's flight to Carthage), 4 (his departure from Carthage, after Jupiter reminded him of his duty to found a new city) and 6 (in which his dead father revealed Roma's destiny)to the emperor and that Book 6 caused is sister Octavia to faint. In 19 BCE he went to Greece to revise the epic, met the emperor in Athens, died in Brundisium, and was buried in Napoli with the inscription "Mantua gave me life, the Calabrians took it away, Naples holds me now; I sang of pastures, farms, and commanders." The emperor ordered Varius Rufus to disregard the dead poet's wishes to burn the poem and to publish it with as few editorial changes as possible. Before long, his poetry became divinatory, as when Publius Aelius Hadrianus used the "Sortes Vergilianae" method of suddenly opening the "Aeneid" and interpreting the resultant passage ("For these no bounds are set, no deadlines drawn" in Book 6) as predicting his adoption by Imperator Caesar Nerva Traianus Divi Nervae filius Augustus and succession to the throne. By the 3rd century Christians also regarded the 4th Eclogue, connecting the imagery of a golden age with the birth of a child, as foretelling the birth of Jesus. By the 12th century the poet was regarded as a great magician; his tomb became a destination of pilgrimages and veneration; the Welsh version of his name, Fferyllt, was a generic term for magic-worker ("fferyllydd" is the modern Welsh word for pharmacist.

ReplyDelete