The Mystic Mariner

In

the days of my youth when

I

had started asking myself questions

About

the riddles of existence,

I

met a mariner, ancient in his ways

And

mystic in his understanding about life.

He

invited me to accompany him

On

a long journey and he would

Give

answers to all my questions.

Like

a kid, I jumped in the air,

Willing

to touch the stars and kiss the clouds.

The

first day, we talked about poetry.

He

said that positive mental energy

Is

found in the verses of great poets

Just

like the energy found in the music

Of

Bach or Mozart.

The

following weekend, we discussed religion

He

said that religion and philosophies

Teach

that man can become the Christ,

Buddha,

Shiva and Zoroaster.

While

the dolphins were swimming gracefully

Among

the great waves of the sea,

I

asked the mystic mariner,

“What

is man`s greatest power?”

He

remained quiet for a long time,

Looked

at the sky and replied,

“Silence”

Then

he spoke about training the mind……

“Man

must train his mind to pick up

What

is good, what is right.

The

power of visualization must be used

As

an exceptional talent and gift.

It

must be nurtured and jealously guarded.”

One

Sunday, we were having breakfast

Comprised of fish curry, salads and boiled rice.

I

quietly asked him about diseases

Affecting

man across the planet.

He

became pensive, as if lost in his thoughts,

Then,

he looked at me in the eyes and said,

“Diseases

are often the purification of

Mind

and body from the toxins

That

have been accumulated.

It

is necessary that man suffers from time to time.”

After

a few weeks spent in the company

Of

waves that dance in an interplay of colors vibrant

And

the rays of the sun teasing my half-naked body,

I

was in a happy mood and laughed

For

reasons unknown to me.

The

mystic mariner touched my bare shoulders,

Drew

me closer and closer to him and whispered,

“Keep

laughing, seriousness reduces life.

Be

happy darling, I love you.”

“I

love you too honey.”

Since

then, I have spent the rest of my life

In

the bosom of the sea, visiting far away shores

With

my mystic mariner as companion.

-- Walter Hallenborg

The Ancient Mariner -- Patrick Anthony Pierson

Mask of the Ancient Mariner -- Patrick Anthony Pierson

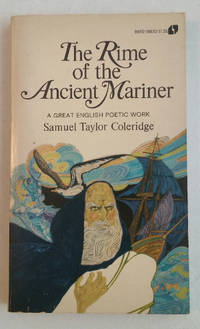

While Samuel Taylor Coleridge was walking with his friends William and Dorothy Wordsworth they discussed George Shelvocke's 1726 narrative "A Voyage Round The World by Way of the Great South Sea," an account of his 1719-1722 privateering expedition against the Spanish and his shipwreck on Más a Tierra ("Closer to Land")(modern Robinson Crusoe Island off the coast of Chile, where Alexander Selkirk had been marooned from 1704-1709 -- the inspiration for Daniel Defoe's 1719 novels The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner" and its sequel "The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe; Being the Second and Last Part of His Life, And of the Strange Surprizing Accounts of his Travels Round three Parts of the Globe"). It included an account of the slaying of a black albatross by his 2nd-in-command. William Wordsworth suggested that Coleridge should write a poem about "spectral persecution" by "the tutelary spirits" as a consequence of "some crime," such as the needless slaying of the albatross. By the time the trio finished their walk, the poem had taken shape in Coleridge's ind, and he wrote "The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere" in 1797-98. It was included in the seminal "Lyrical Ballads, with a Few Other Poems" (1798) by Wordsworth and Coleridge. In the course of the poem the assassin and the crew were mercilessly punished for his deed until he achieved an ecological epiphany. The mariner's last words were:

ReplyDeleteHe prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

Though Wordsworth quibbled about some aspects of the poem, such as "the old words and the strangeness" of the narrative and "that the imagery is somewhat too laboriously accumulated," and suggested that it be replaced by "some little things which would be more likely to suit the common taste" if a 2nd edition were published, he nevertheless included it in the 2nd edition despite Coleridge's own objections, claiming that it contained "many delicate touches of passion, and indeed the passion is every where true to nature, a great number of the stanzas present beautiful images, and are expressed with unusual felicity of language; and the versification, though the metre is itself unfit for long poems, is harmonious and artfully varied, exhibiting the utmost powers of that metre, and every variety of which it is capable. It therefore appeared to me that these several merits (the first of which, namely that of the passion, is of the highest kind) gave to the Poem a value which is not often possessed by better Poems."